Introspective Magazine: Hudson River Estate

1stDIBS: INTROSPECTIVE MAGAZINE

HOME TOURS

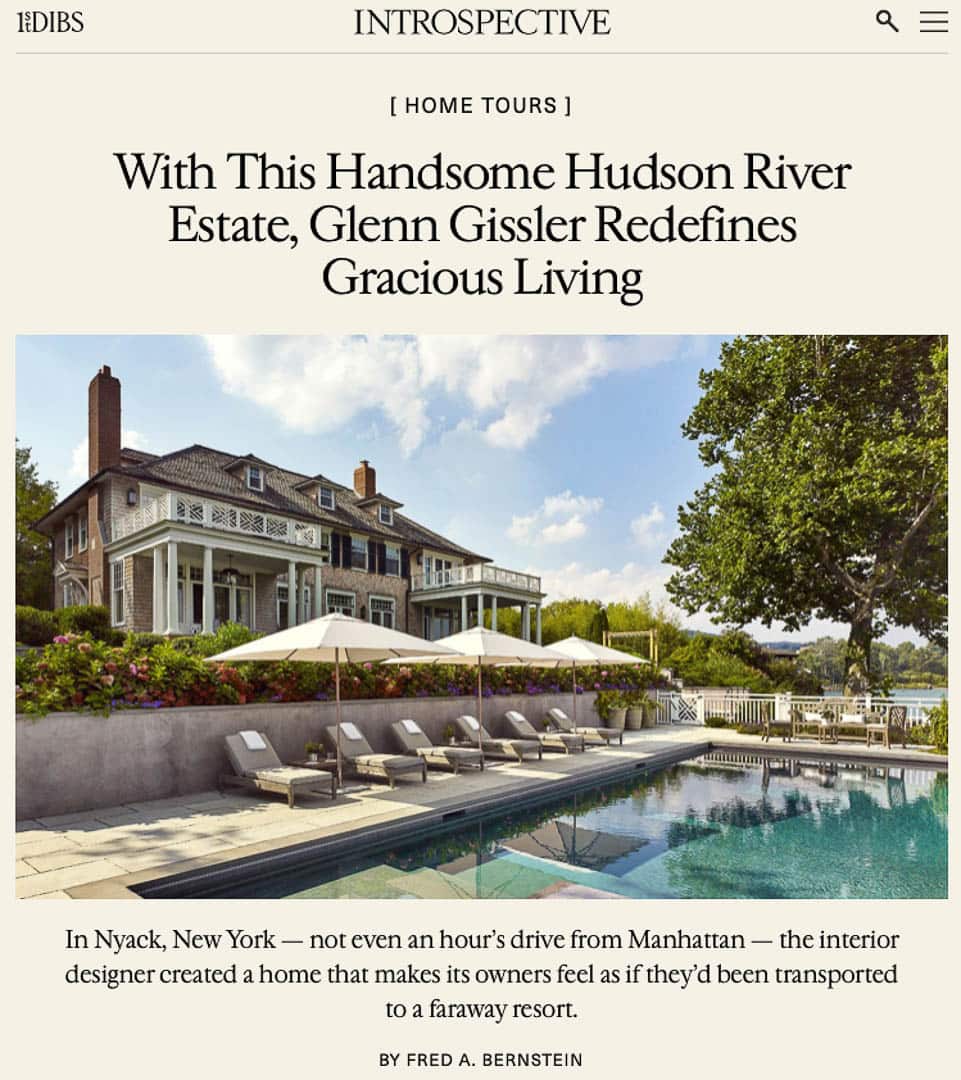

With This Handsome Hudson River Estate, Glenn Gissler Redefines Gracious Living

by Fred A. Bernstein

Photography by Peter Murdock

In Nyack, New York — not even an hour’s drive from Manhattan — the interior designer created a home that makes its owners feel as if they’d been transported to a faraway resort.

JUNE 12, 2022

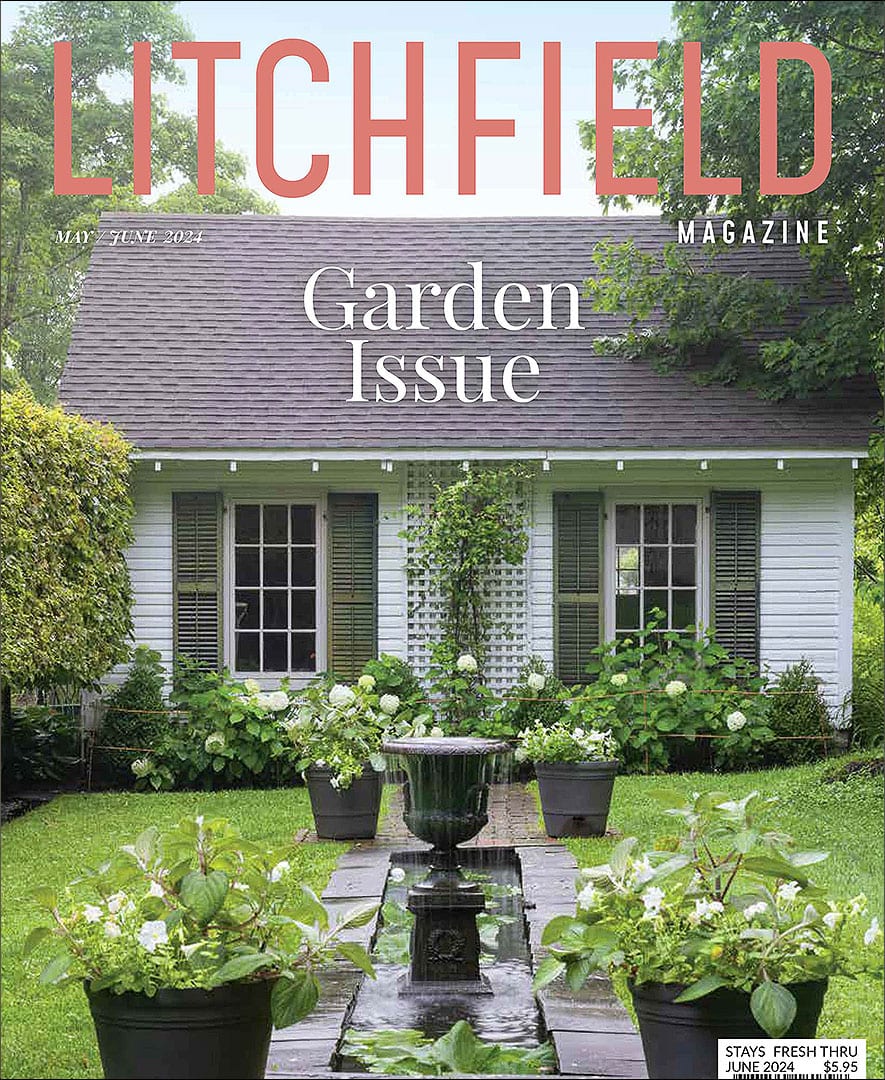

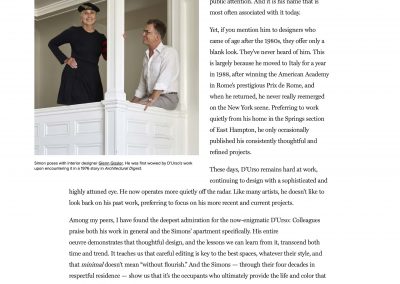

It takes GLENN GISSLER almost two hours to drive from his apartment in Brooklyn Heights to his weekend house in northwestern Connecticut. So, he might envy his clients — an investment banker, his wife and their young daughter — who live in a Lower Manhattan loft. Getting to their weekend house, in Nyack, New York, takes all of 45 minutes. And that includes crossing the Hudson River, which the city apartment and the country house overlook from opposite sides.

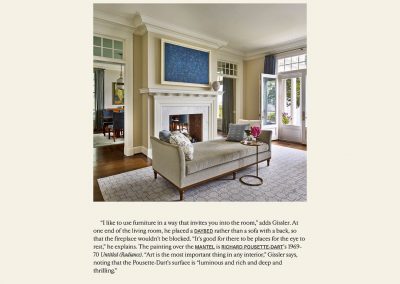

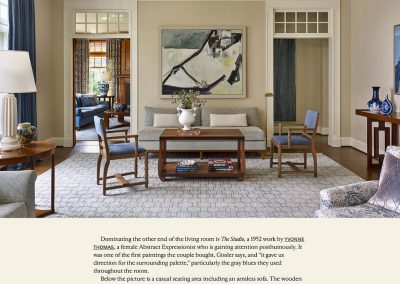

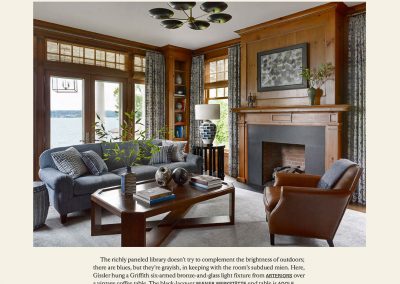

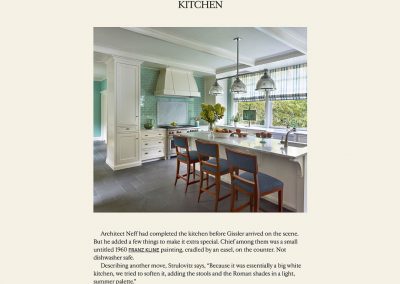

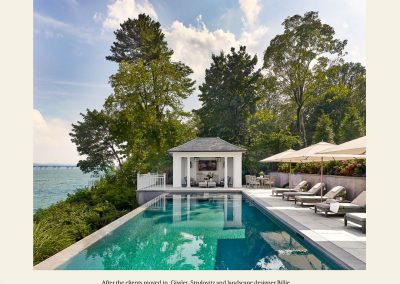

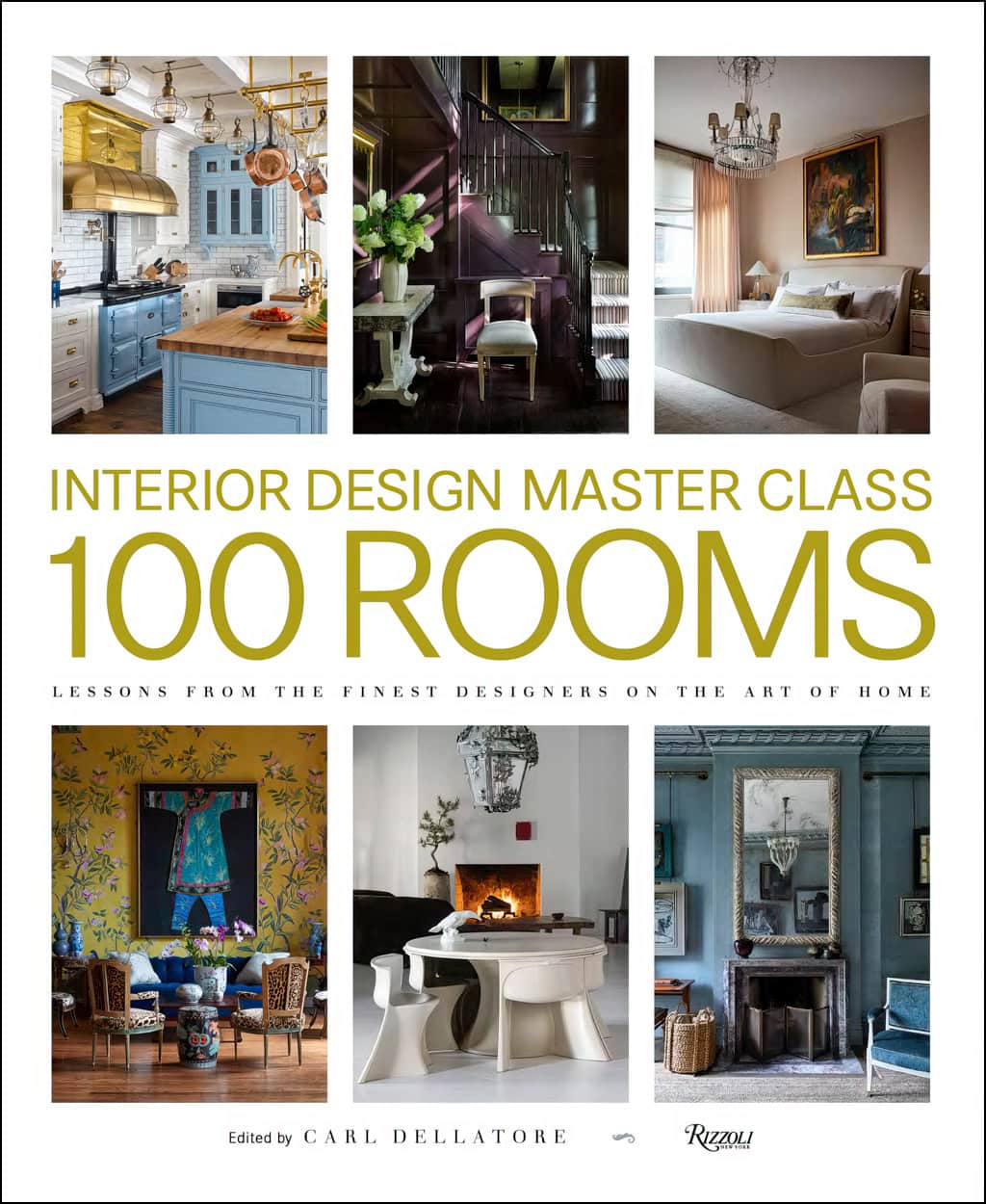

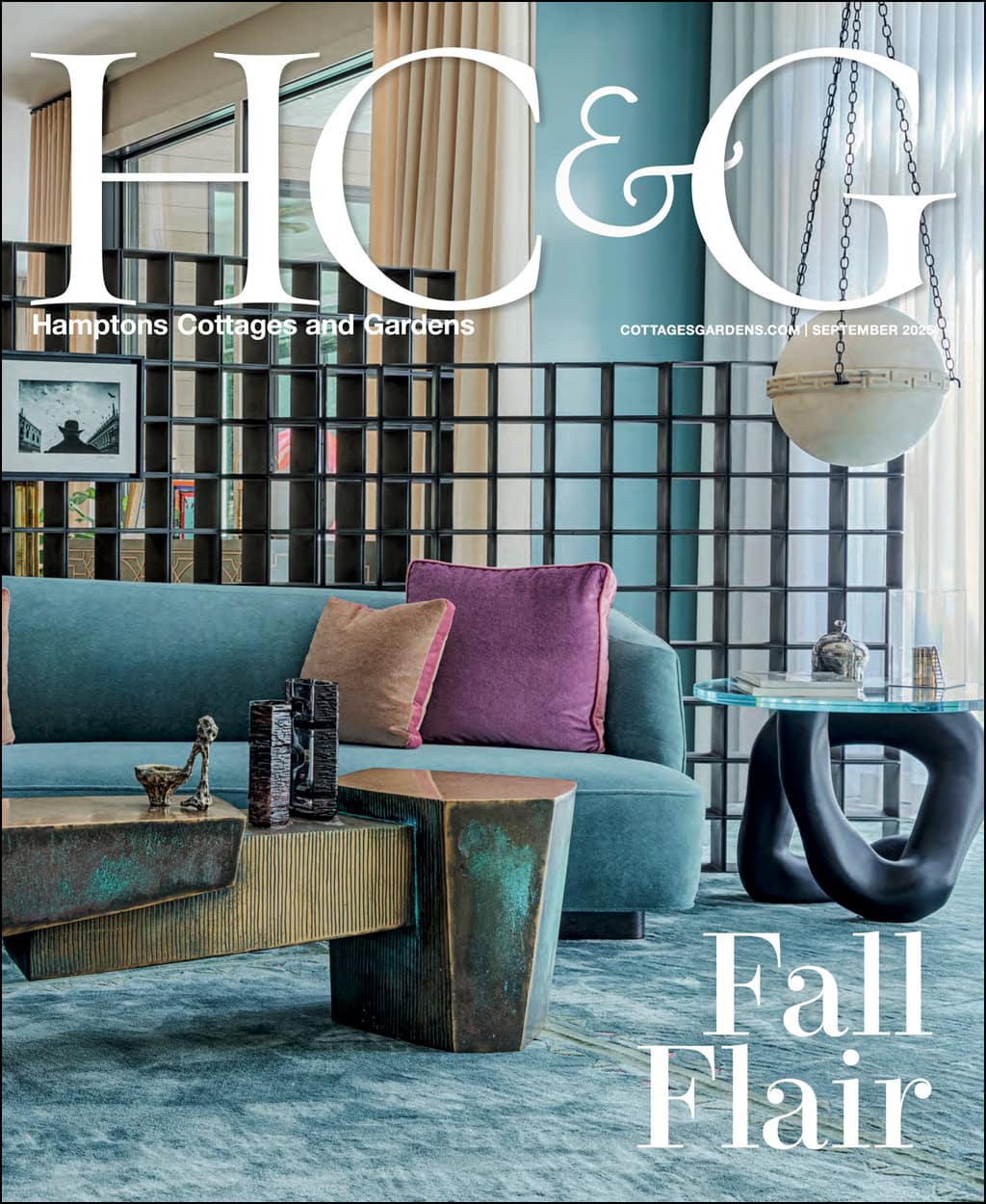

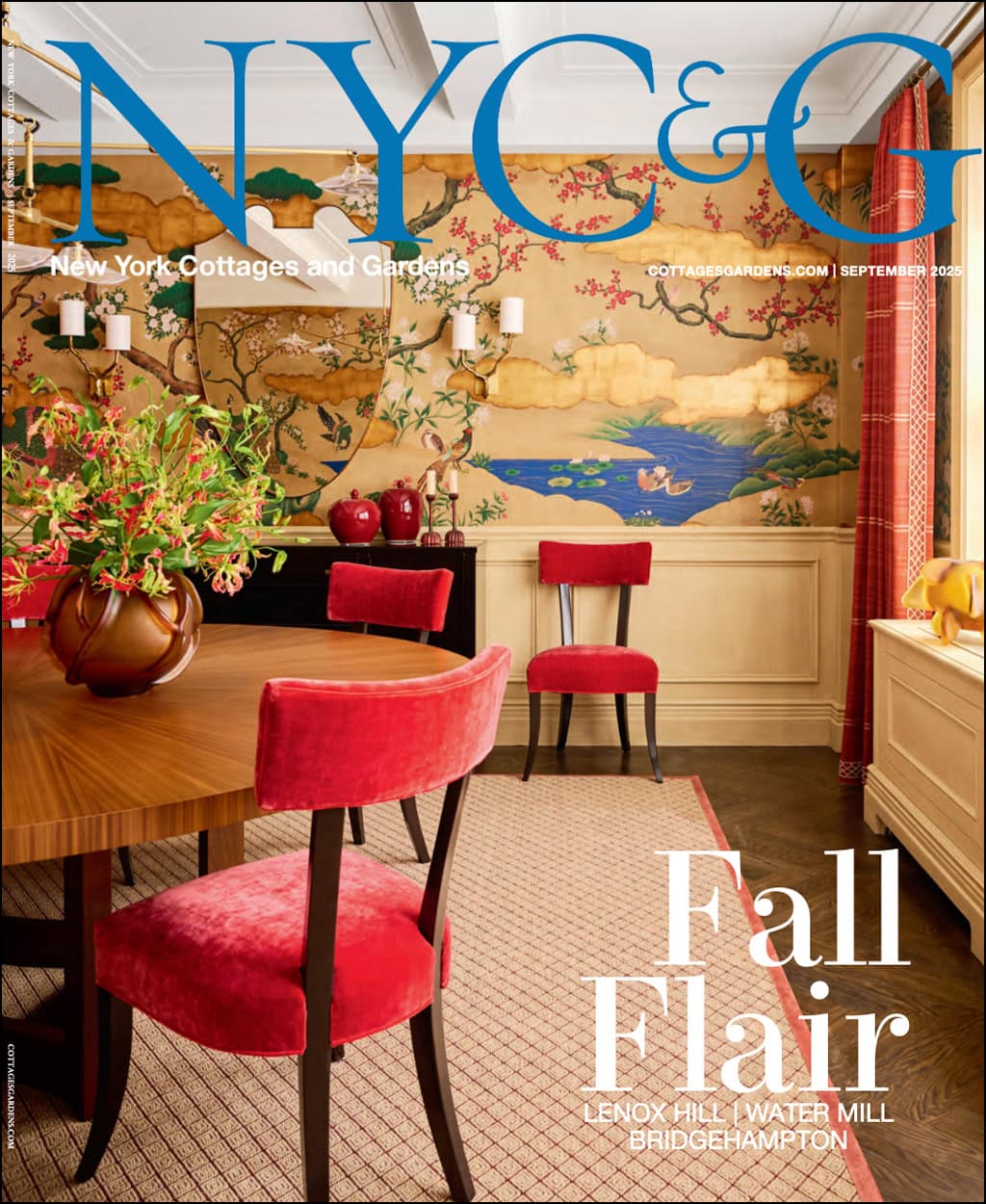

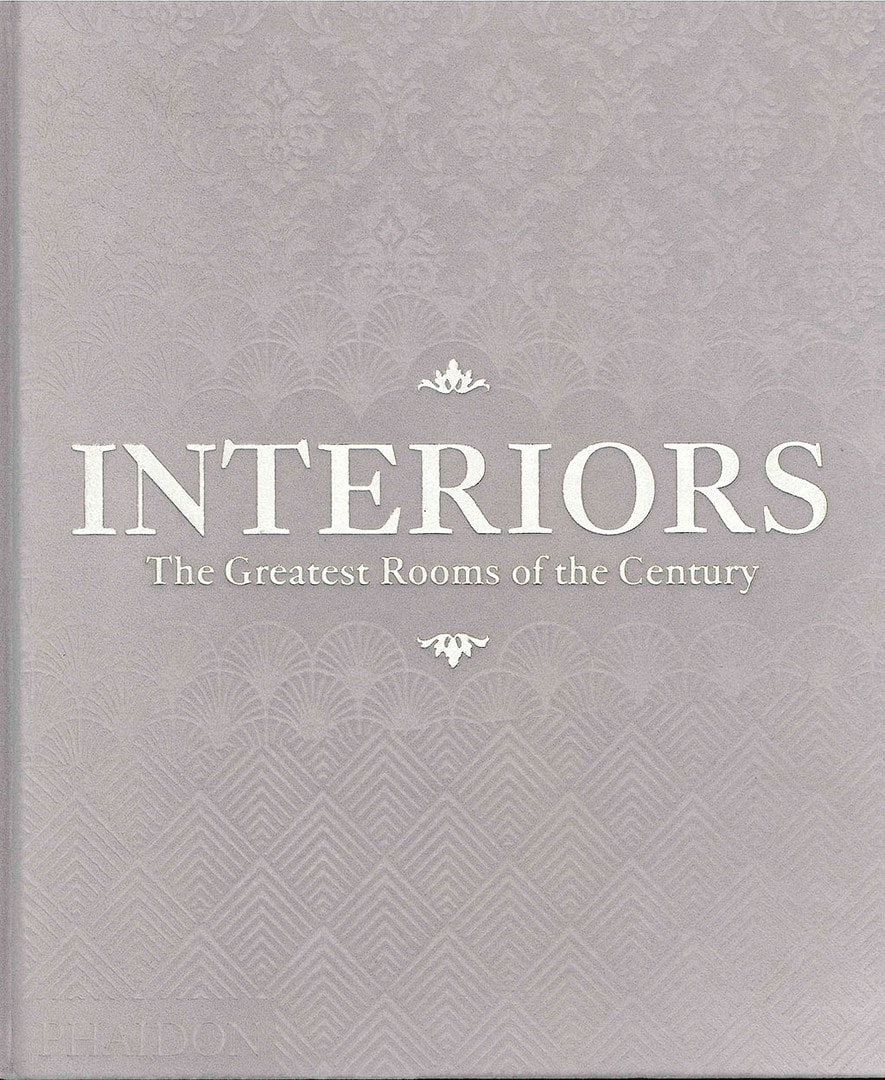

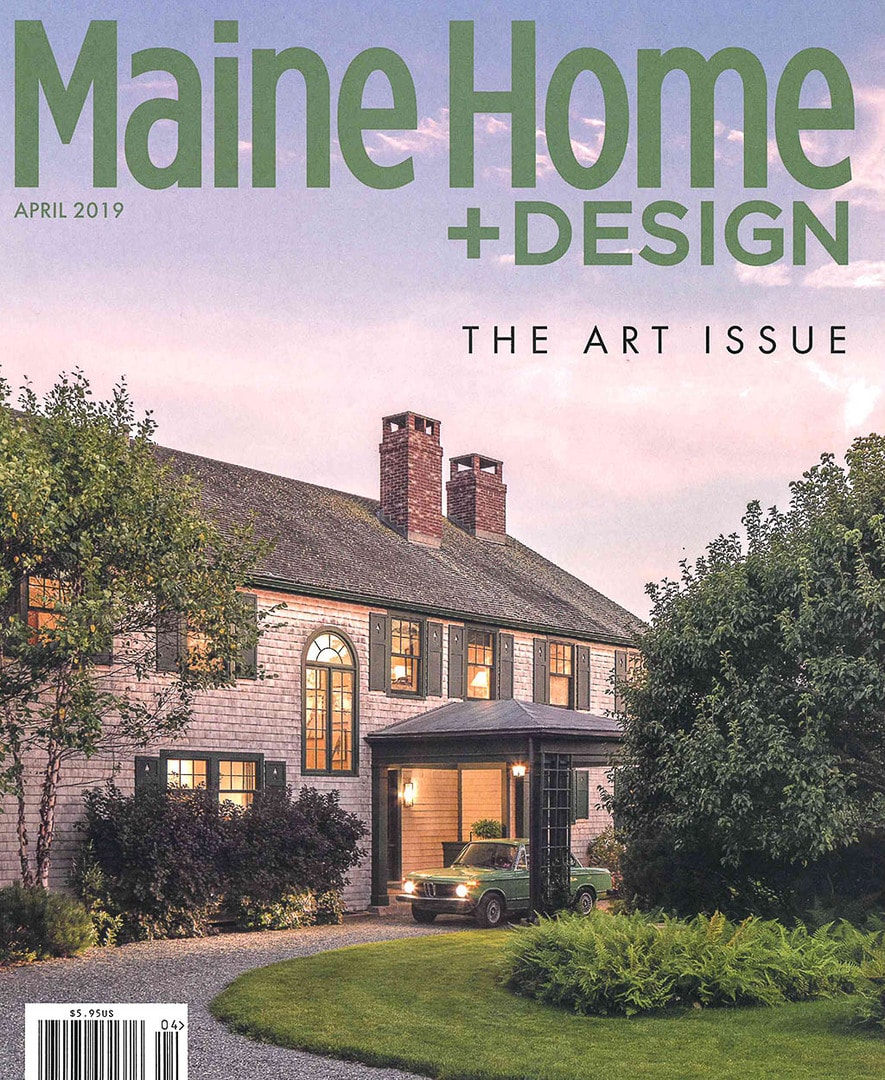

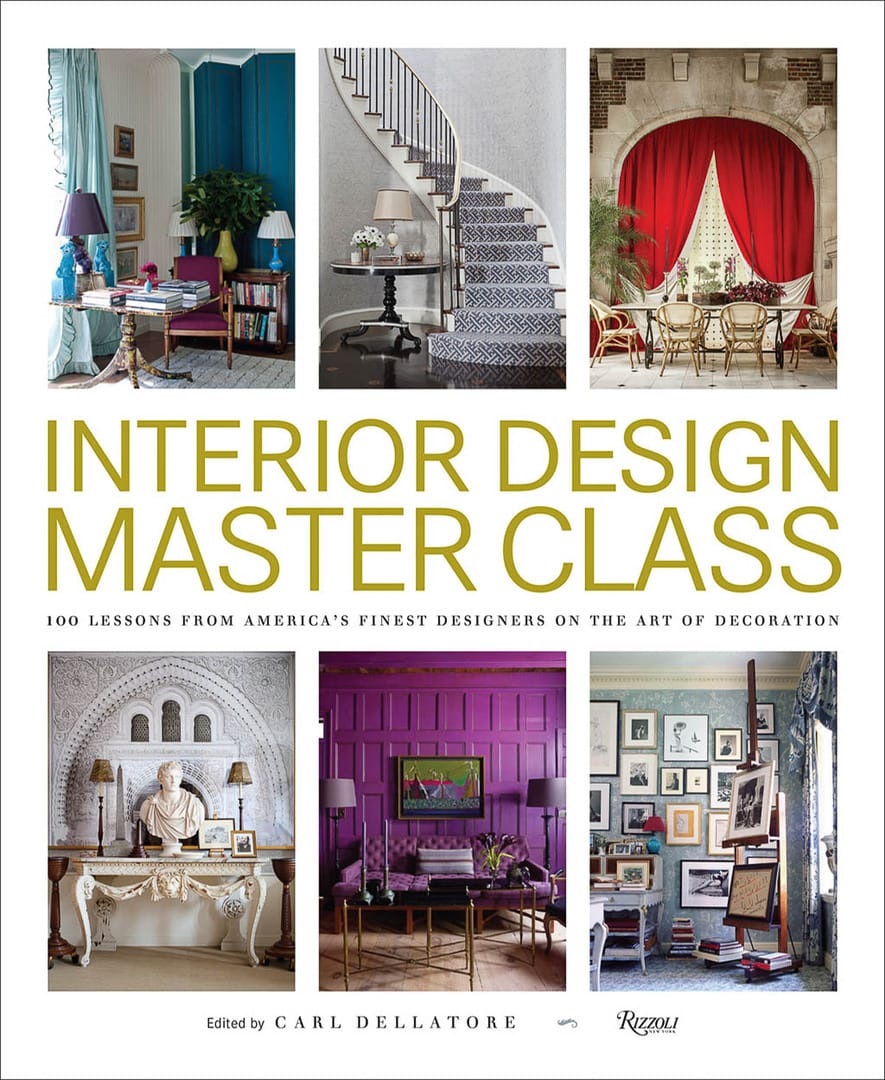

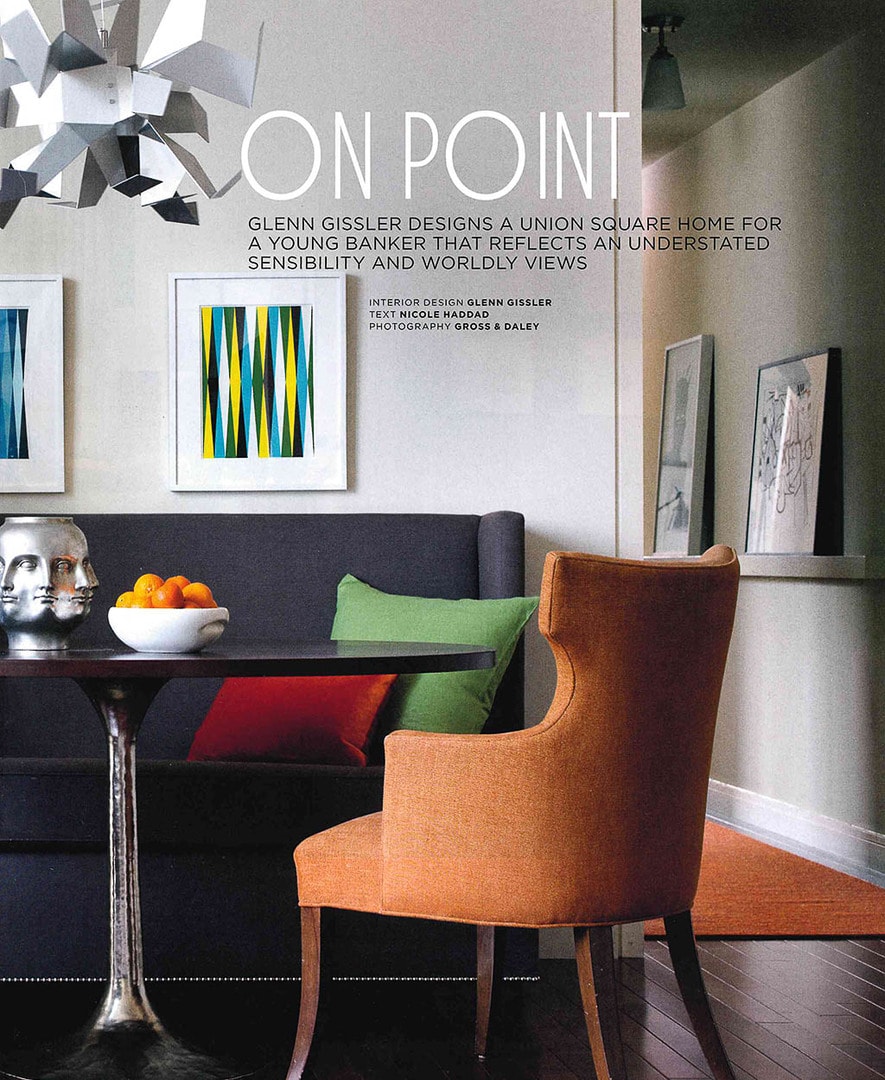

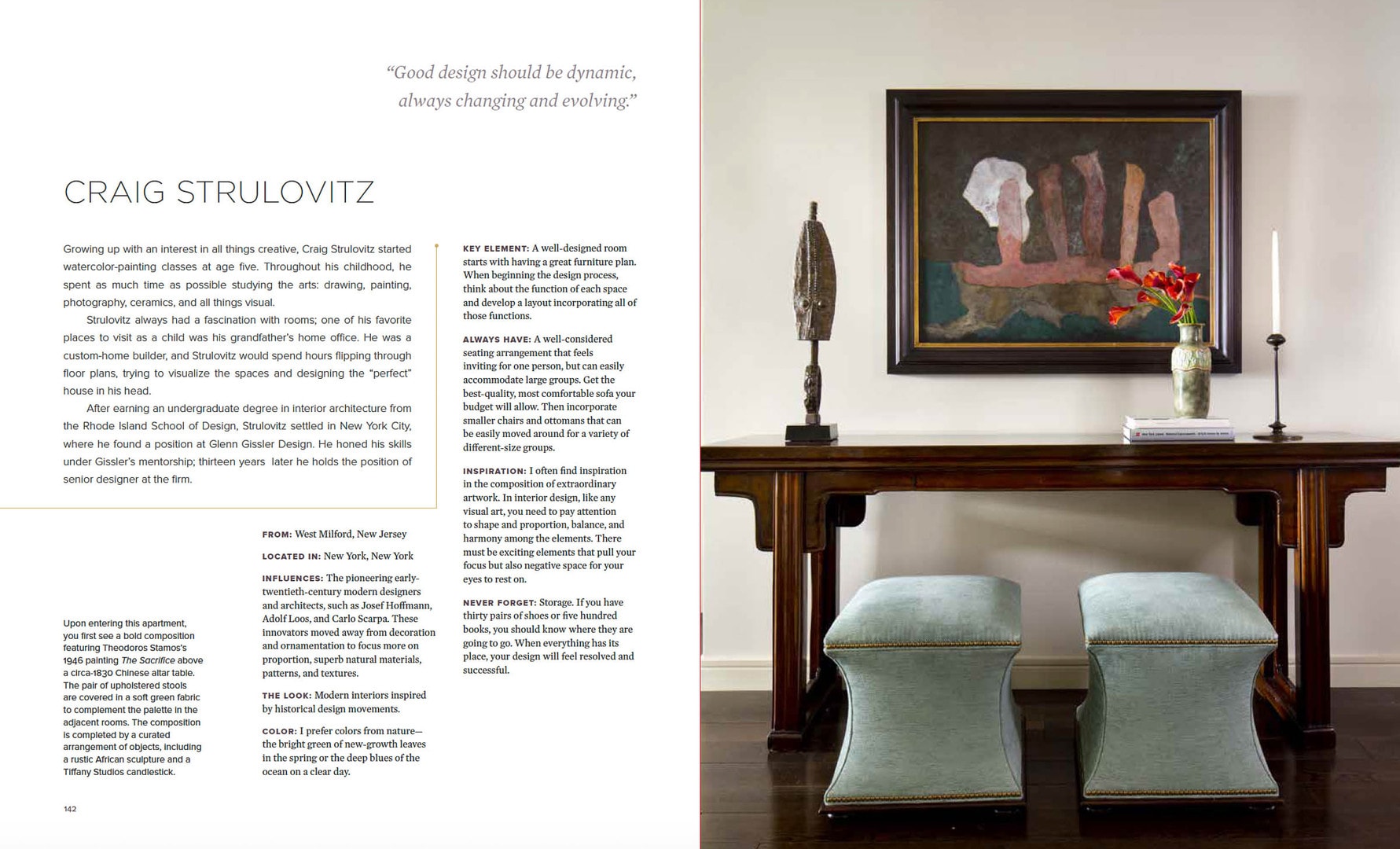

Nine years ago, when they bought the Manhattan apartment, the couple hired Gissler to design its interiors, a job that included helping them assemble a collection of ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONIST ART. Then, three years ago, when they started looking for a weekend house, they turned to Gissler for advice. After a few false starts, the couple found a newly constructed COLONIAL REVIVAL/shingle-style home that fronts the river at its widest point. Architect David Neff had given the 5,200-square-foot home traditional details while keeping the interiors open and light.

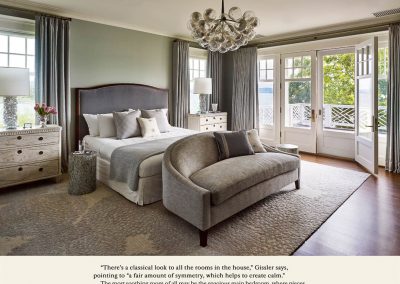

“The rooms are well proportioned, not too grandiose,” Gissler says. And the setting couldn’t be better. The house, he says, is set high enough to offer spectacular Hudson River views and low enough to feel close to the water.

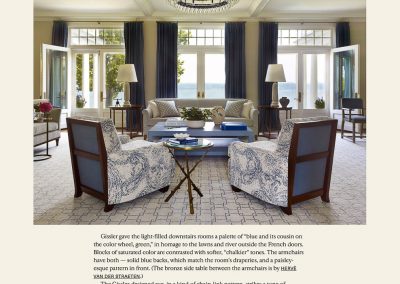

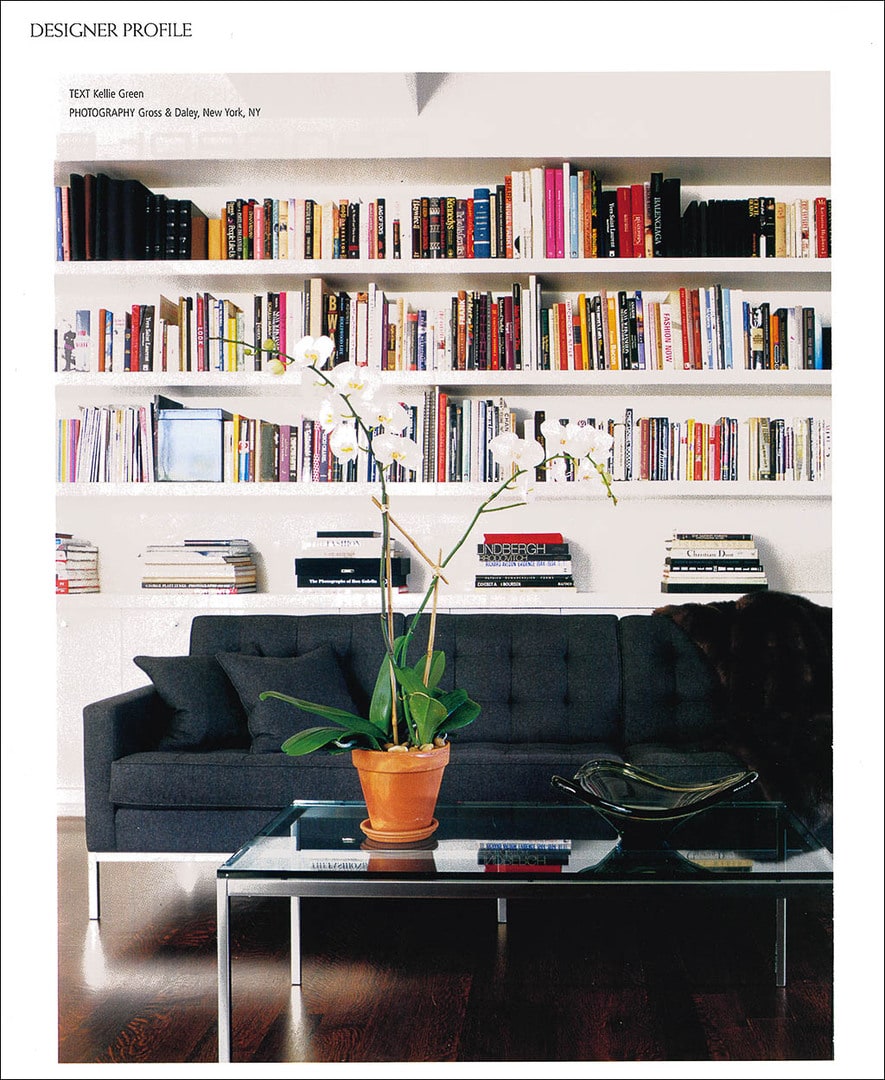

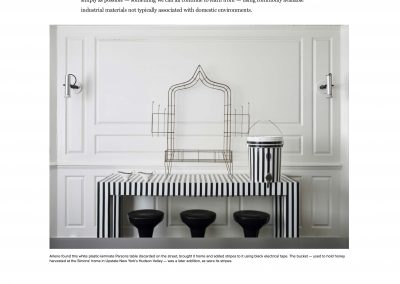

The couple bought it, and Gissler proceeded to outfit the interiors with a smart mix of new and old furniture, much of it European. “The house is very much American, but it’s not AMERICANA,” says the designer, who studied architecture and fine arts at the Rhode Island School of Design, then worked for an architect (Rafael Viñoly) and an interior designer (JUAN MONTOYA) before founding his own practice, in 1987.

Here, Gissler leads Introspective on a tour of the house, on which he collaborated with his senior designer, Craig Strulovitz, also a RISD graduate.

Read the full Article on 1stdibs.com