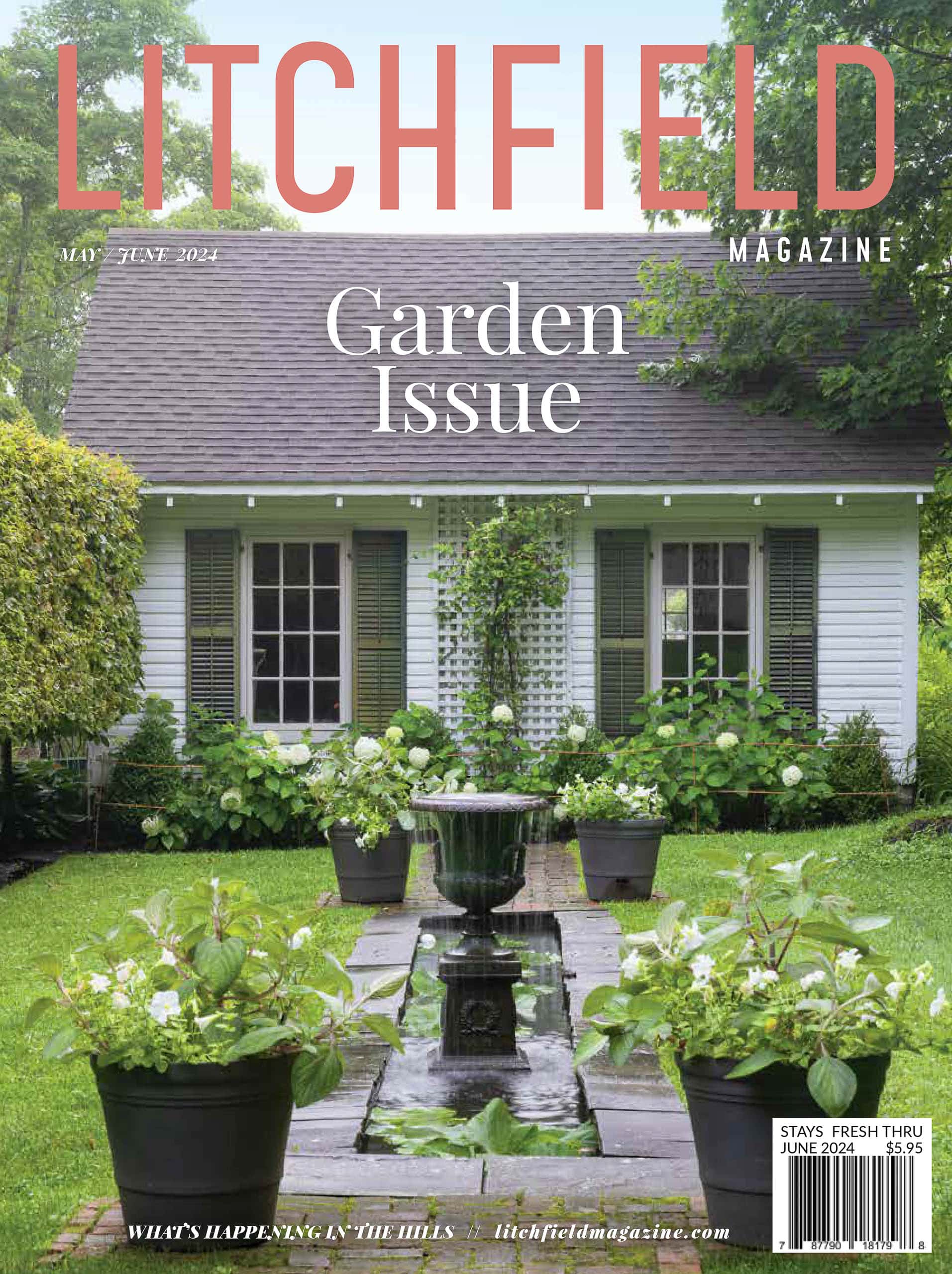

Litchfield Magazine

litchfield magazine

MAY JUNE 2024

Just What the Doctor Ordered

An 1810 Roxbury Antique Gets a 21st Century Makeover

By Jamie Marshall

Photos by Ryan Lavine and Gross & Daley

Published on litchfieldmagazine.com

It was love at first sight for Patricia Yarberry Allen when she stepped into the antique Greek Revival on South Street in Roxbury. “You know how people say they get struck by a certain house and they just know?” she says. “I just knew.”

Part of the appeal was the location on the edge of the town’s historic district. Part was the finished basement. But the biggest draw? The view. “When I stepped inside I could see all the way from the front entrance out through the dining room windows to a sloping lawn and trees and out to a very large pond. I felt like I was home.”

Precocious, smart, and driven (her friends call her a force of nature), Yarberry Allen started working at a local hospital before she was 16. “I lied about my age,” she says. She moved to New York after medical school to complete her internship and residency at Cornell-New York Hospital before going on to establish the thriving women’s health practice she still runs today.

In 2015, she and her husband Douglas McIntyre, a founder of digital media sites and consultant for nonprofits, sold a vacation house in Palm Beach and rented a mid-century modern in Litchfield County hoping to find something to buy. “The topography reminds me of southcentral Kentucky,” she says. “Except that every two miles, you see a sign for an Episcopal church instead of a Baptist church.”

As soon as they settled on Roxbury property, Yarberry Allen turned to her good friend and neighbor, New York City-based designer, Glenn Gissler, to bring their vision to life. The goal? “Sophisticated, comfortable, gracious, dramatic, and personal,” says Gissler. “I think we were creating the farmhouse of her youthful dreams.” One by one, he ticked all the boxes. Among the priorities—space for books and clothes. Both Yarberry Allen and her husband are voracious readers.“I’ve known Pat for about 40 years. She buys good clothes and she still has all of them,” he says.

Most of the interior work involved “architectural corrections,” which were done by a local contractor, Ryan Fowler. He also reconfigured the attic into a proper third floor, lined two walls of one sitting room with bookshelves, and created a storage pantry for Yarberry Allen’s tabletop collection.

Much of the furniture was repurposed from her former homes. The foyer chandelier came from a Madison Avenue duplex she owned in the ‘80s. “Initially that foyer had rough-hewn beams and columns and with the amazing chandelier, we needed to make the space a little more formal,” Gissler says. “We painted the wood paneling aubergine. It’s a dramatic color. She’s not afraid of it at all.” The sitting room couches are dressed in an aubergine linen from Romo, while the club chairs are done in a gray floral by Kravet.

Though she’s not a fan of window treatments, “I have no interest in fussy stuff,” Yarberry Allen says—she made an exception in the primary suite. “Glenn gave me these beautiful cream-colored linen drapes. I wake up in the morning and pull them back and the sun hits my eyes while I’m having my breakfast. It’s an oasis.”