Brownstoner

BROWNSTONER

SPRING/SUMMER 2018

A sophisticated duplex is a designer’s repository of art and antiques, a haven for its owner and a splendid space for entertaining

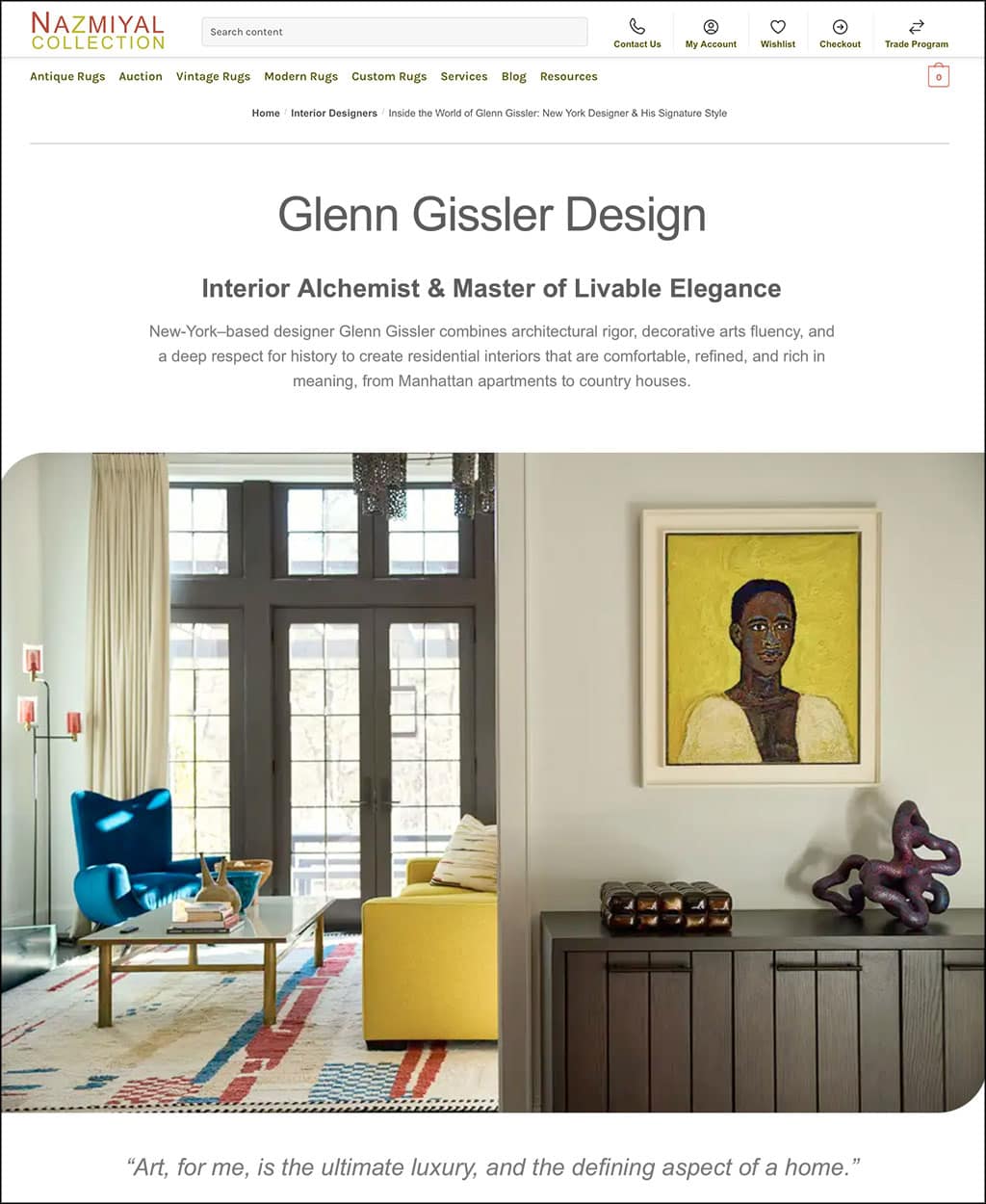

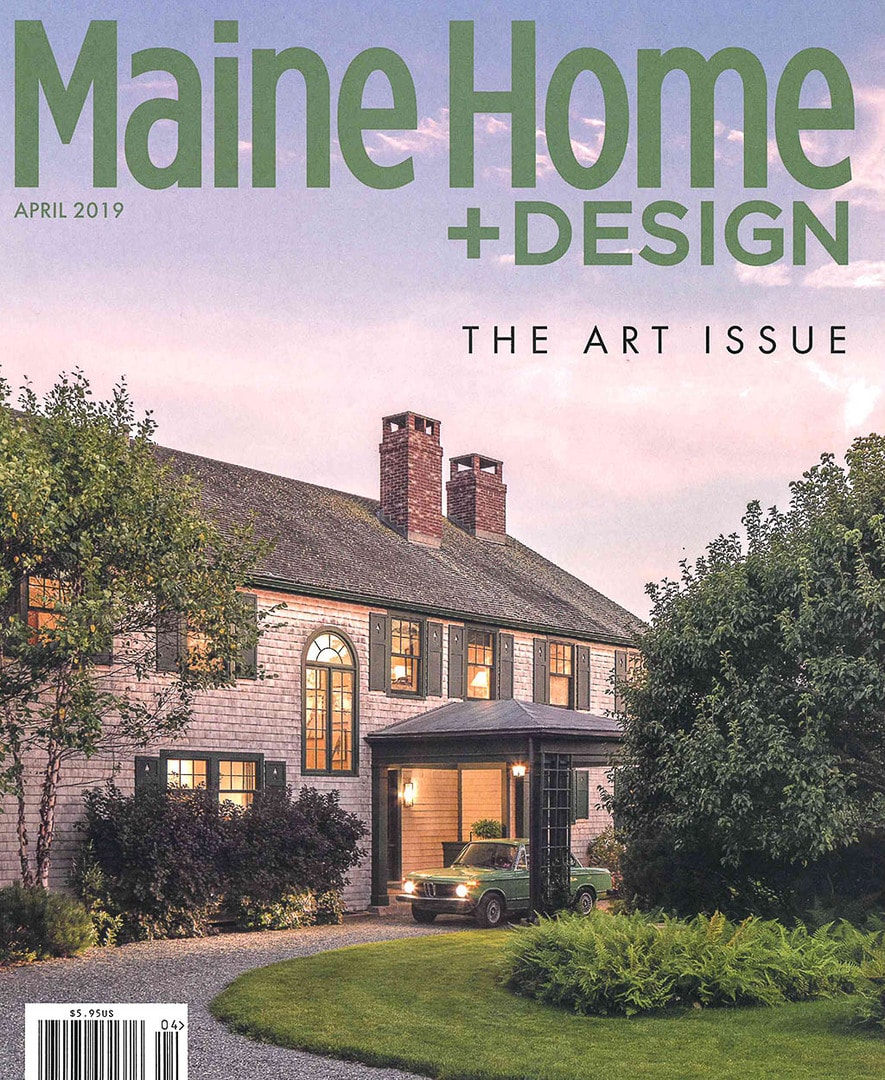

When interior designer Glenn Gissler went apartment hunting six years ago, the longtime Manhattanite had been to Brooklyn very few times before. He was astounded by the charm and amenities he found in the upper duplex of a circa 1890 row house in central Brooklyn Heights. “The apartment exceeded my list of ‘must haves,’” Gissler says, recalling his initial reaction: “You mean I can have all this—two floors, a fireplace, a washer-dryer and a terrace—ten minutes from Greenwich Village?!”

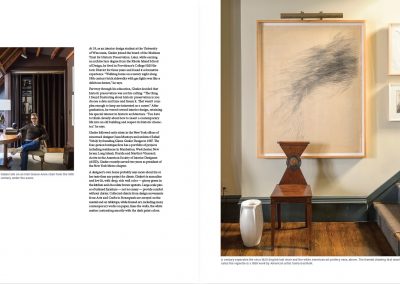

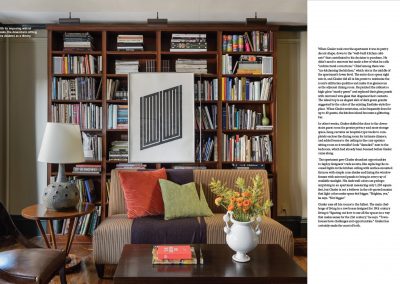

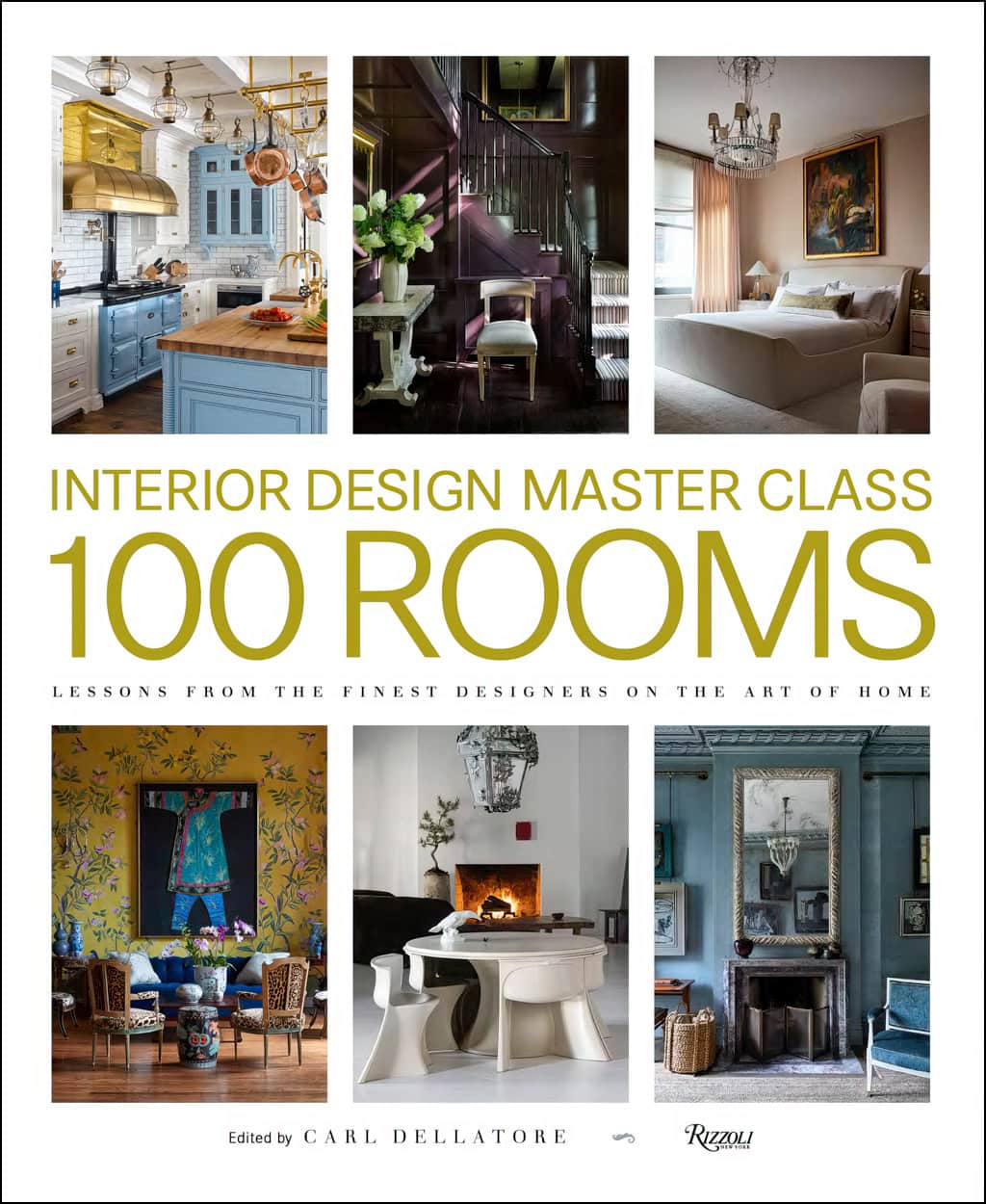

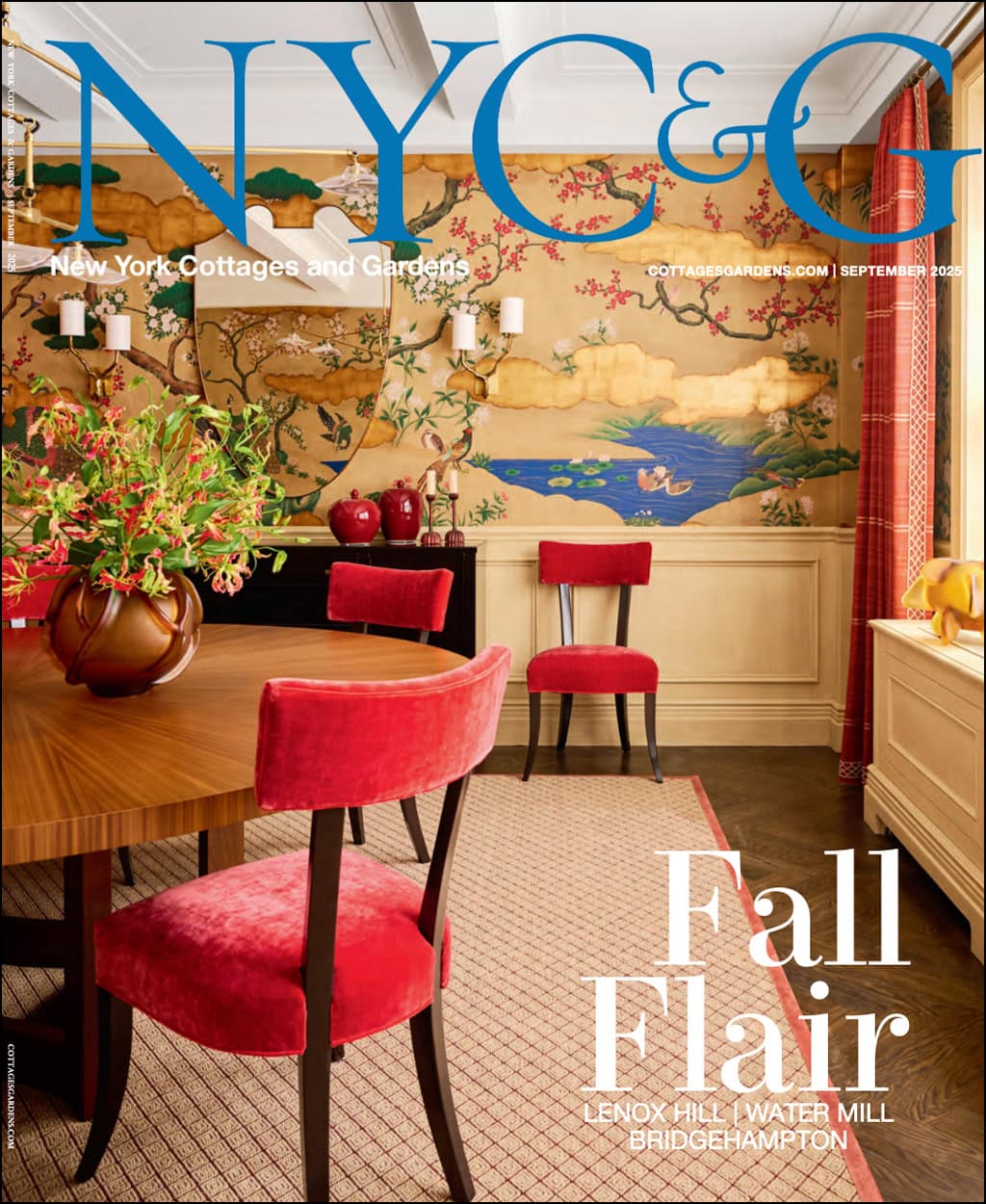

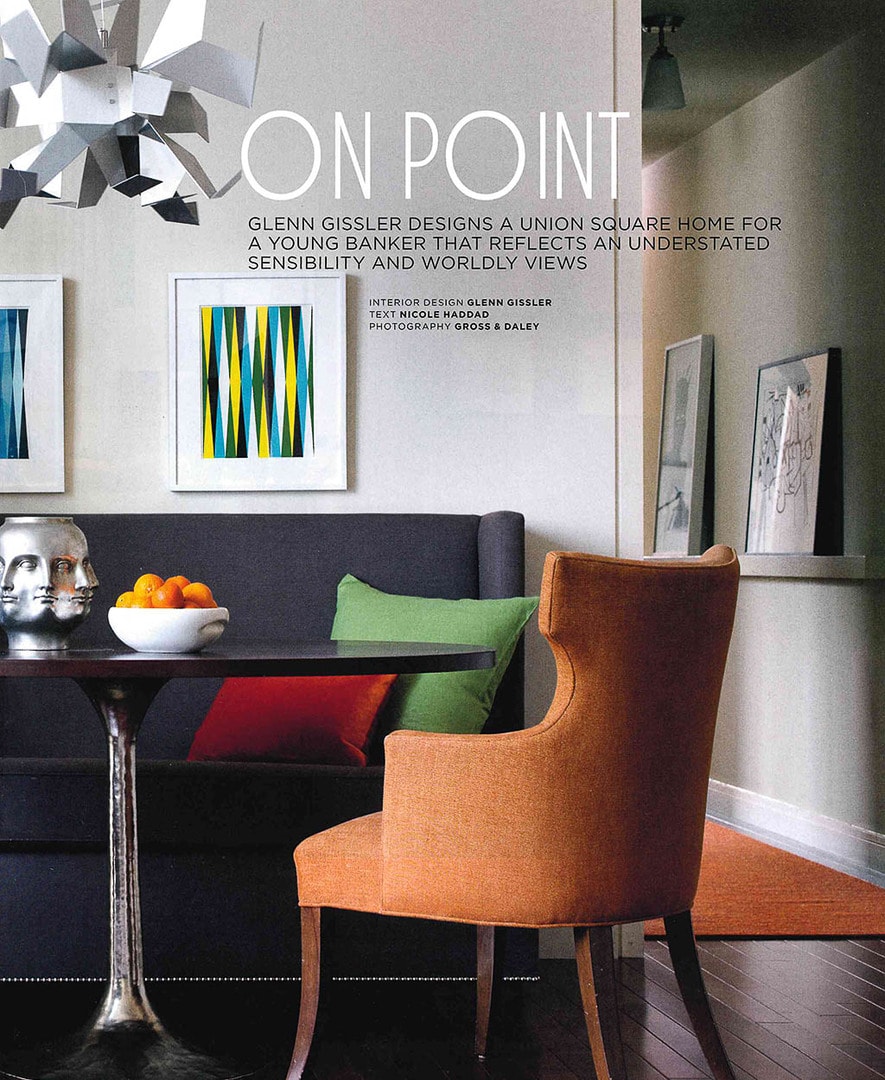

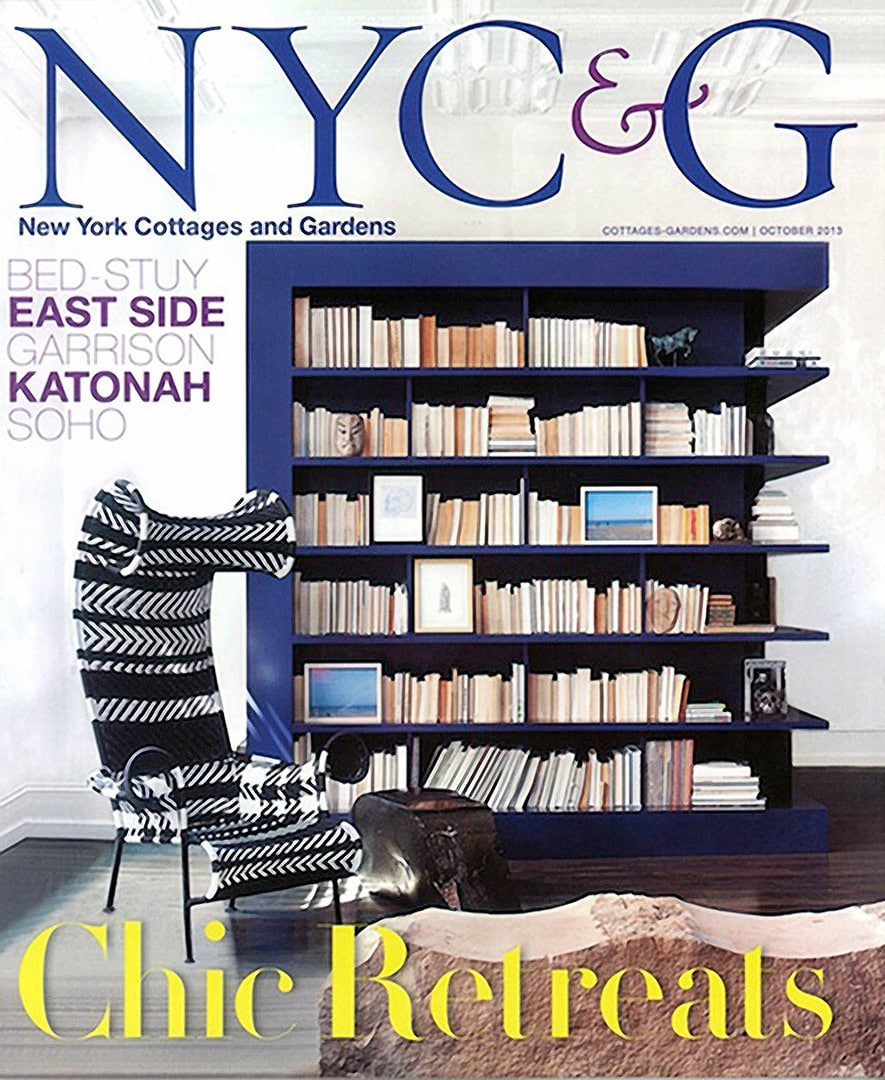

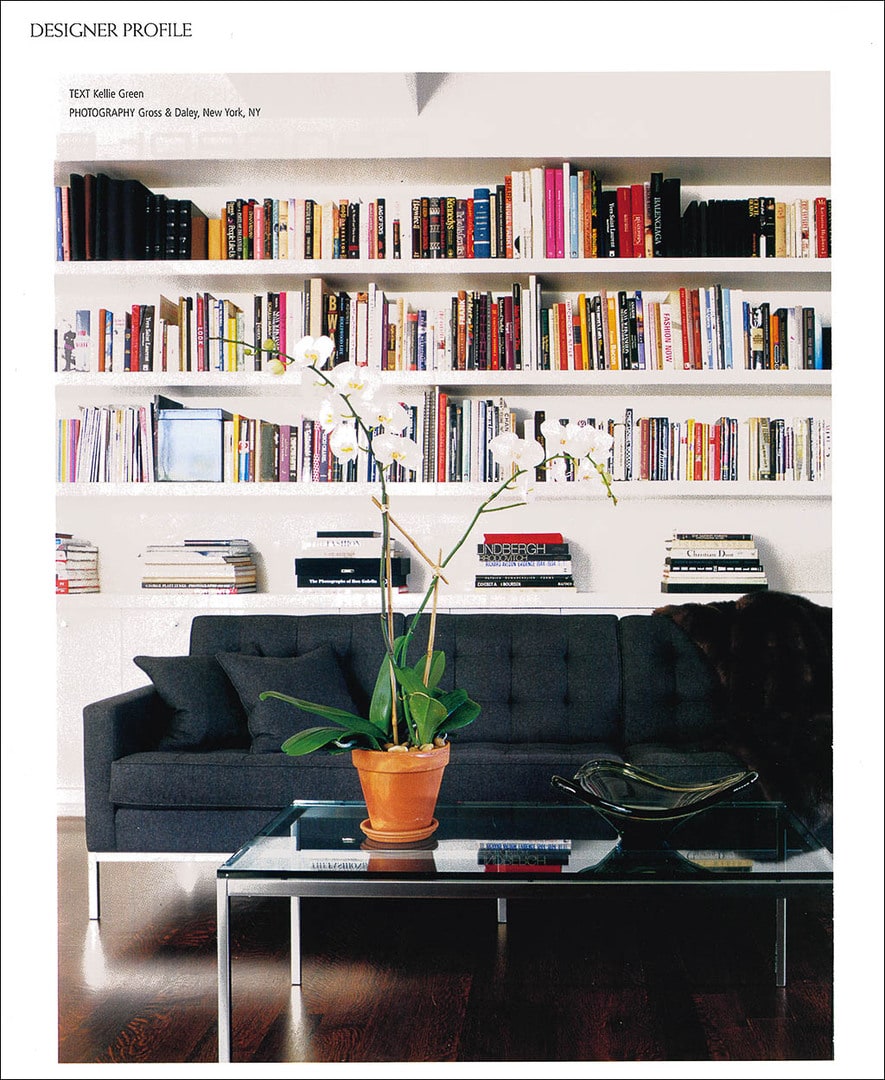

Now, furnished and decorated with what Gissler calls a “collage of art and artifacts,” the two-bedroom co-op is even more enviable. Sleek and cozy, modern and historic at the same time, it comprises a book-lined dining room, kitchen and guest room on the lower level, and two rooms with beamed ceilings, reminiscent of a Paris stelier. And who wouldn’t want to wake up to a view of a terrace filled with greenery?

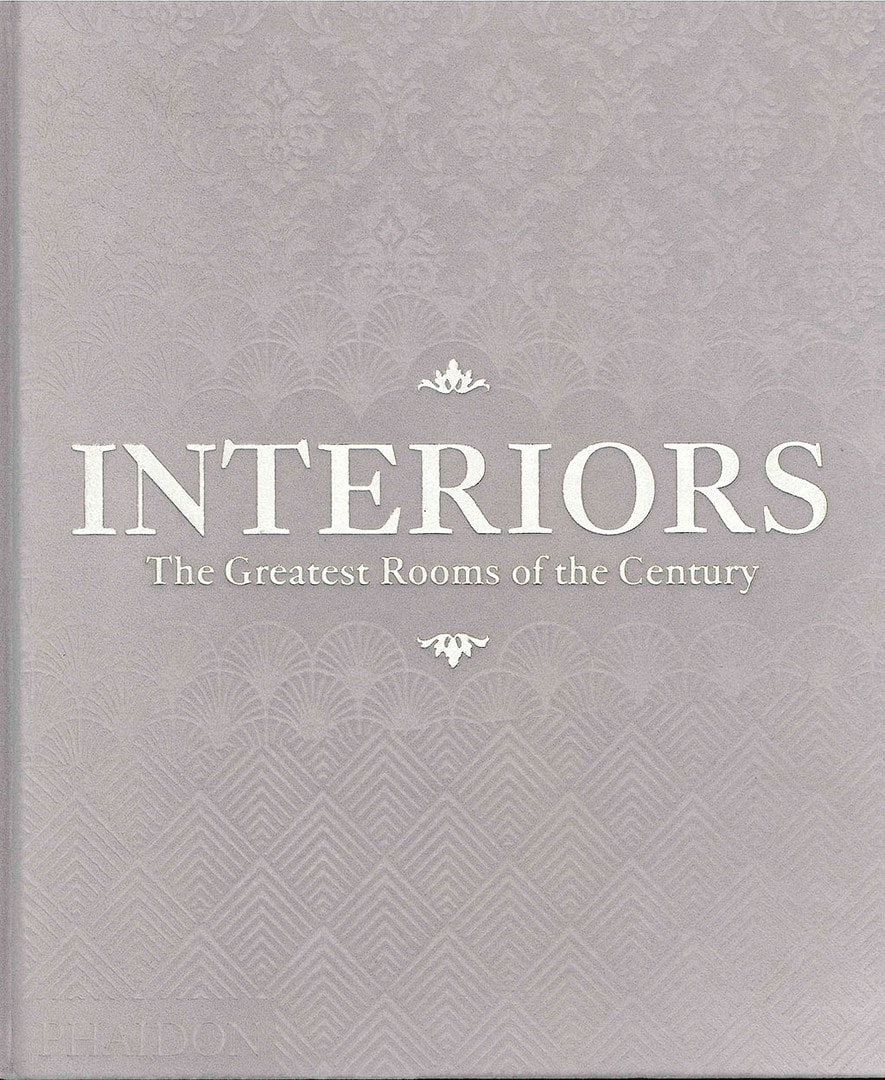

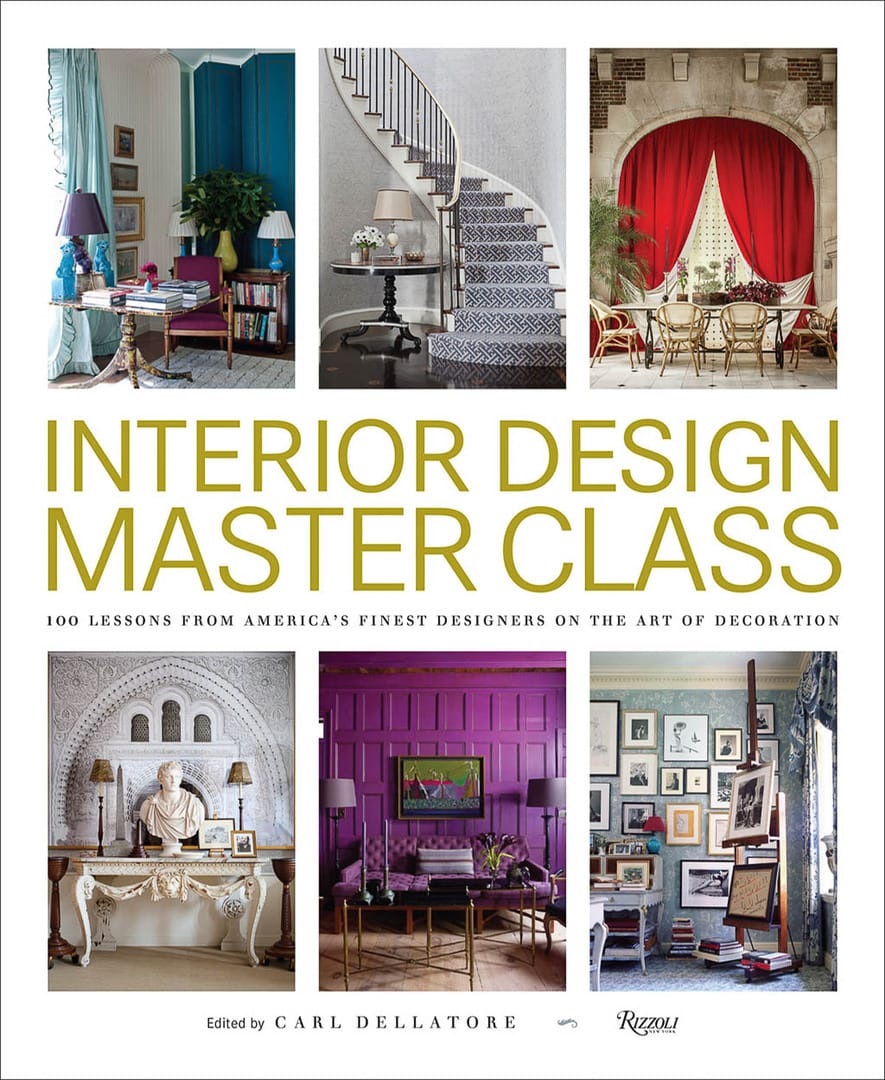

Gissler’s atmospheric apartment, filled with intriguing places representing styles and periods from antiquity to the present day, is “a distillation of the designer’s development over the past three decades,” as the designer’s website puts it. Every item, from millicl-old clay pots to a Swedish mid-century lamp resembling a meteorite, from a Keith Haring poster given to Gissler by the artist at an anti-nukes demonstration his first summer in New York to framed childhood drawings by his now-teenage daughter, reflects who he is (an eBay addict, to be sure) and where he comes from. “Their cash value is irrelevant,” he says. “It’s whether it speaks to me.”

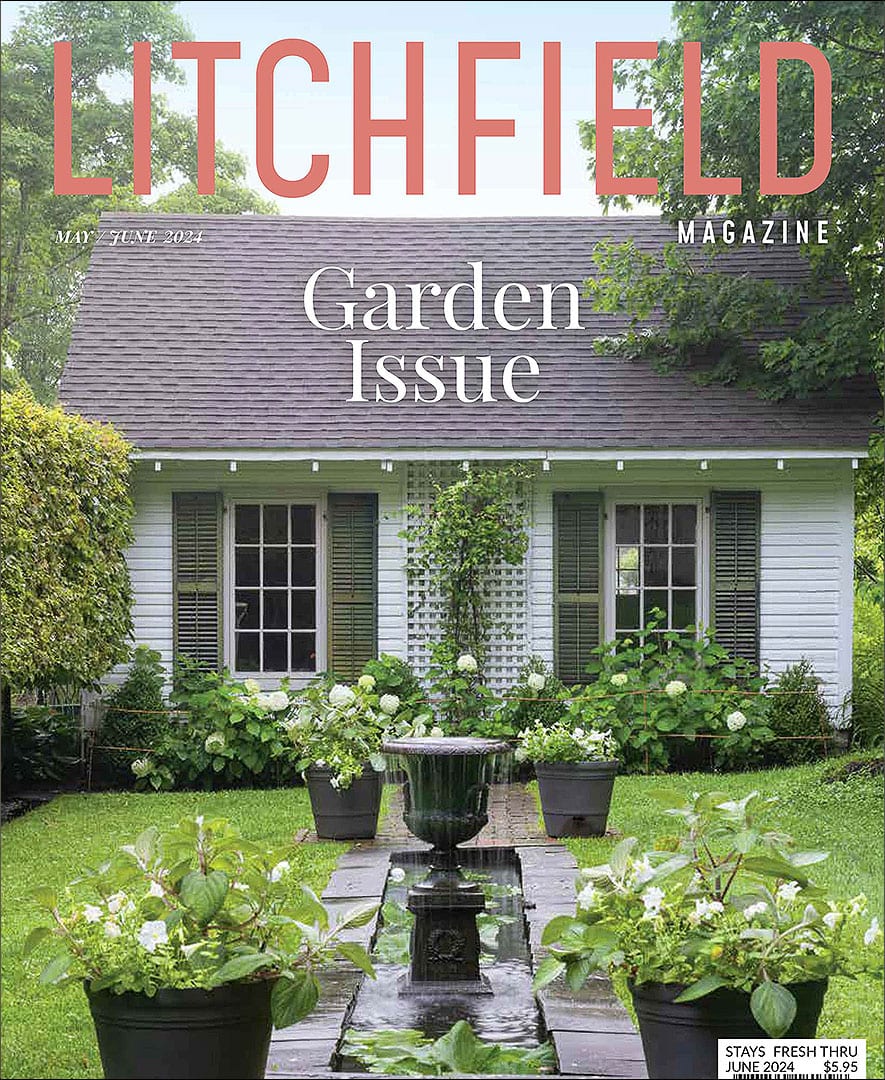

It was inevitable that Gissler would end up living in a vintage house (he also owns a 1840s farmhouse on eight aces in Connecticut). He saved his first building at the age of 18—a Gilded Age Milwaukee mansion he rescued by convincing his father, then an editor of Milwaukee’s largest daily newspaper, to write an opinion piece embarrassing the bankers who had refused to lend $200,000 to a preservation group to buy the building and keep it from destruction. The banks changed their tune and the Pabst Mansion still stands as a historic house museum.

At 19, as an interior design student at the University of Wisconsin, Gissler joined the board of the Madison Trust for Historic Preservation. Later, while earning an architecture degree from the Rhode Island School of Design, he lived in Providence’s College Hill Historical District for three years and found it a formative experience. “Walking home on a snowy night along 18th century brick sidewalks with gas lights was like a delirious dream,” he says.

Part way through his education, Gissler decided that historic preservation was not his calling. “The thing I found frustrating about historic preservation is you choose a date and time and freeze it. That wasn’t complex enough to keep me interested as a career.” After graduation, he veered toward interior design, retaining his special interest in historic architecture. “You have to think cleverly about how to insert a contemporary life into an old building and respect its historic character,” he says.

Gissler followed early stints in the New York offices of renowned designer Juan Montoya and architect Rafael Vinholy by founding Glenn Gissler Design in 1987. The four-person boutique firm has a portfolio of projects including residences in Manhattan, Westchester, New Jersey, Long Island, Florida and Martha’s Vineyard. Active in the American Society of Interior Designers (ASID), Gissler recently served two years as president of the New York Metro chapter.

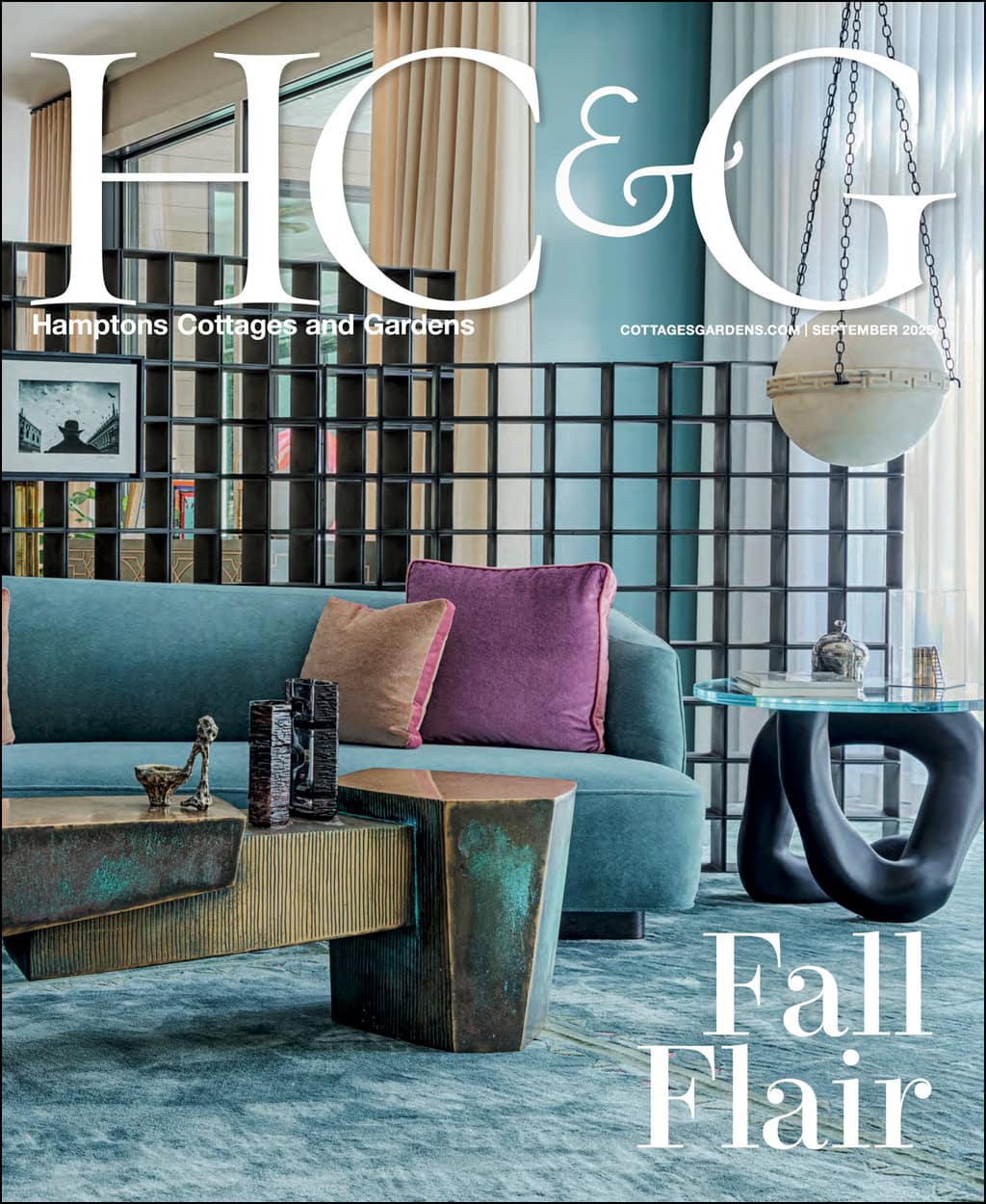

A designer’s own home probably says more about his or her taste than any project for clients. Gissler’s is masculine and low lit, with deep, rich wall color–glossy green in the kitchen and chocolate brown upstairs. Large-scale pieces of tailored furniture—not too many—provide comfort without clutter. Collected objects from design movements from Arts and Crafts to Steampunk are arrayed on the mantle and on tabletops, while framed art, including many contemporary works on paper, line the walls, the white mattes contrasting smartly with the dark paint colors.

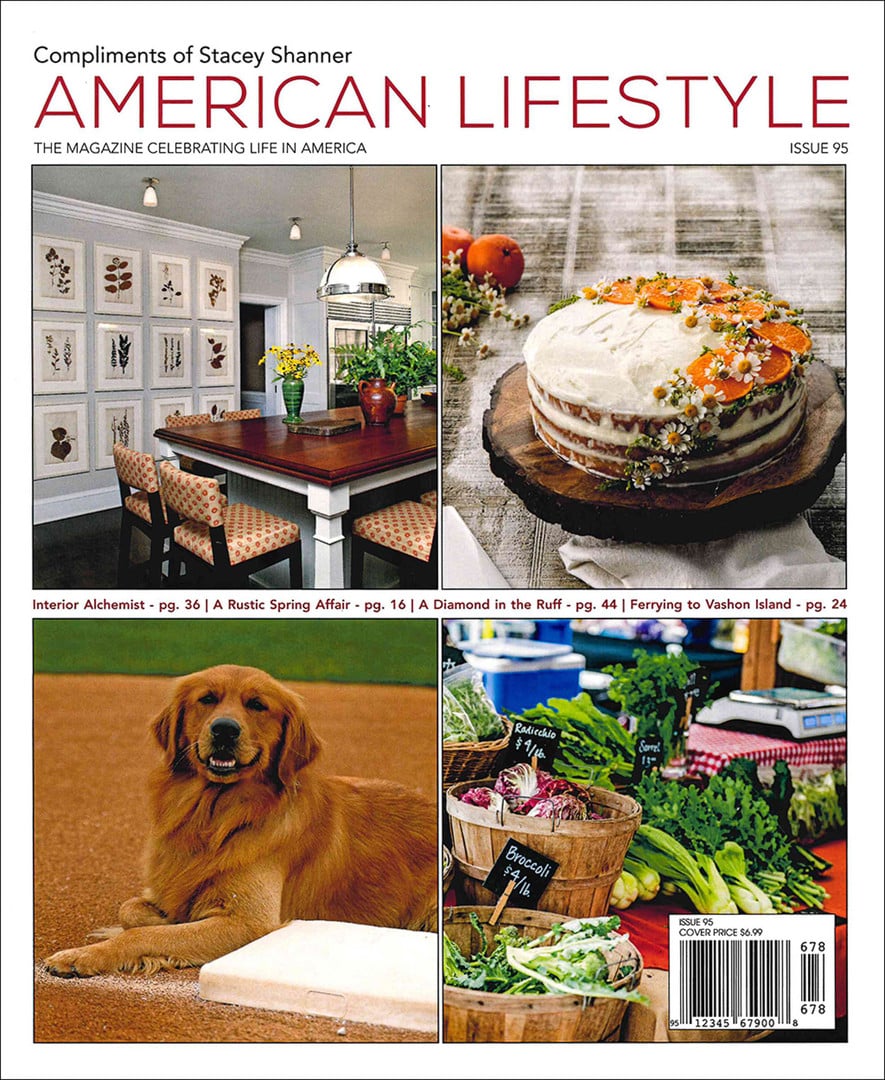

When Gissler took over the apartment it was inn pretty decent shape, down to the “well-built kitchen cabinets” that contributed to his decision to purchase. He didn’t need to renovate but made a few of what he calls “architectural corrections.” Chief among them was “un-kitchening the kitchen,” which sits in the middle of the apartment’s lower level. The entry door opens right into it, and Gissler did all in his power to minimize the room’s utilitarian qualities and makes it as glamorous as the adjacent dining room. He painted the cabinets as high-gloss “murky green” and replaced their glass panels with mirrored wire glass that disguises their contents. The island top is an elegant slab of dark green granite suggested by the color of the existing Eastlake-stye fireplace. When Gissler entertains, as he frequently does for up to 40 guests, the kitchen island becomes a glittering bar.

In other tweaks, Gissler shifted the door to the downstairs guest room for greater privacy and more storage space, hung curtains on hospital-type tracks to completely enclose the dining room for intimate dinners, and added beams to the ceiling int he cozy upstairs sitting rom so it wouldn’t look “denuded” next to the bedroom, which had already beamed before Gissler came along.

The apartment gave Gissler abundant opportunities to deploy designers’ trade secrets, like replacing the recessed lights in the kitchen ceilings with surface- mounted fixtures with simple cone shades and lining the window frames with mirrored panels to bring in every ray of available sunlight. His dark wall colors are perhaps surprising in an apartment measuring only 1,250 square feet, but Gissler is not a believer in the oft-quoted maxim that light colors make spaces feel bigger. “Brighter, yes,” he says. “Not bigger.”

Gissler uses all his rooms to the fullest. The main challenge of living in a row house designed for 19th century living is “figuring out how to use the spaces in a way that makes sense for the 21st century,” he says. “Town-houses have challenges and opportunities.” Gissler has certainly made the most of both.

Story: Cara Greenberg

Photography: Matthew Williams

Styling: Vanessa Vazquez